Erratum: A qualitative cross-sectional study exploring the implementation of disability-inclusive WASH policy commitments in Svay Reing and Kampong Chhnang Provinces, Cambodia

- 1London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 2International Centre for Evidence in Disability (ICED), London, United Kingdom

- 3WaterAid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

- 4Royal University of Phnom Penh, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

- 5WaterAid Australia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Background: The Government of Cambodia references core concepts of human rights of people with disabilities in their water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) policies and guidance. However, few references clearly articulate activities to achieve these.

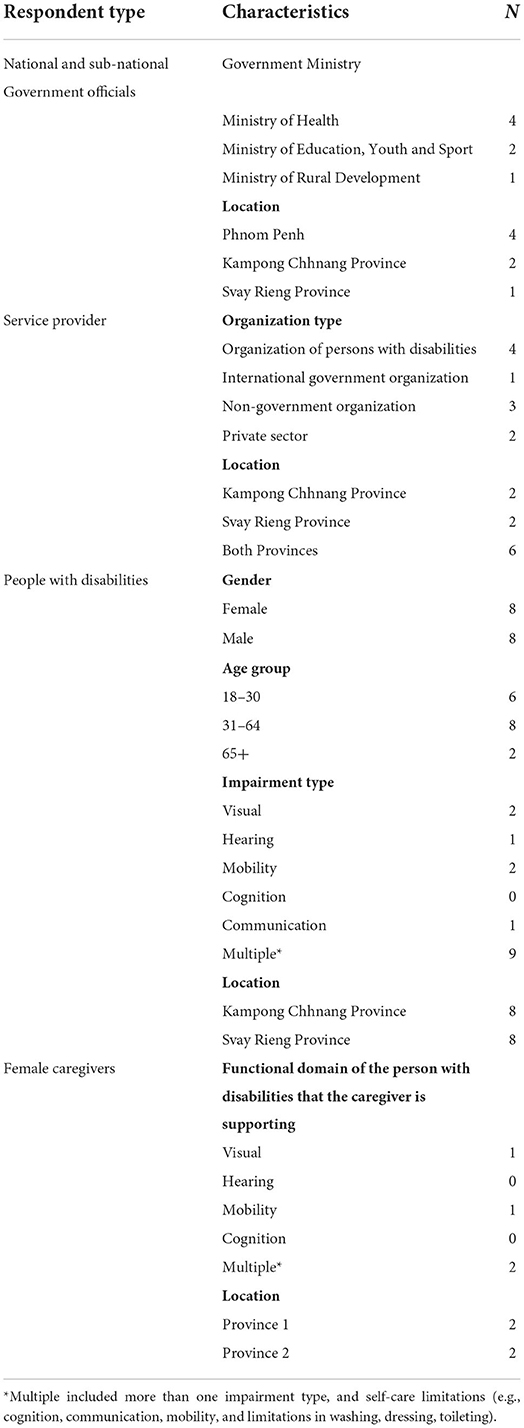

Methods: This cross-sectional study in Cambodia explores the implementation of core concepts of human rights referenced in Cambodia's WASH policies in Kampong Chhnang and Svay Reing Provinces: Individualized services, Entitlement/affordability, Participation, Family resource, Access. Seven government officials and 10 service providers working in Phnom Penh and the two provinces, 16 women and men with disabilities (aged 18–65+), and four caregivers living in the study sites were included. Purposive sampling was applied to select participants. In-depth interviews were conducted via Zoom and over the telephone and analyzed data thematically using Nvivo 12.

Results: The Three Star Approach for WASH in Schools was noted as a promising approach for implementing policy commitments to make school WASH services accessible. However, policy commitments to disability-inclusive WASH were not always enacted systematically at all levels. Organizations of Persons with Disabilities faced challenges when advocating for disability rights at WASH sector meetings and people with disabilities were inconsistently supported to participate in commune WASH meetings. Poor access to assistive devices (e.g., wheelchair) and inaccessible terrain meant few people with disabilities could leave home and many had inadequate WASH services at home. Few could afford accessible WASH services and most lacked information and knowledge about how to improve WASH access for people with disabilities. Caregivers had no guidance about how to carry out the role and few had assistive devices (e.g., commodes, bedpans) or products (i.e., lifting devices), so supporting WASH for people with disabilities was physically demanding and time-consuming.

Conclusion: This study has noted several areas where Cambodia's WASH systems are focusing efforts to ensure people with disabilities gain access to WASH, but it has also highlighted aspects where implementation of policy commitments could be strengthened. A more comprehensive and cross-sectoral approach to progressively realizing the rights to water and sanitation for people with disabilities and challenging disability discrimination more broadly could significantly disrupt the vicious cycle of poverty and disability.

Introduction

The global context

Access to safely managed water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services are essential for poverty reduction, health, and wellbeing. Yet worldwide, one in 10 people do not have basic drinking water, one in five people do not have basic sanitation, and almost one in three people are unable to wash their hands with soap and water at home (World Health Organization (WHO) United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2021).

An estimated 15% of the global population has a disability (World Health Organization, 2011). People with disabilities are less likely than people without disabilities to live in households that have access to basic water and sanitation services (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs, 2018). Analyses of intra-household access to these facilities across six countries show that people with disabilities are less able to collect water and use the household toilet independently and are more likely to contact urine and feces when using the toilet than family members without disabilities (Mactaggart et al., 2018, 2021; Banks et al., 2019). Despite limited access, people with disabilities often have additional requirements for WASH. For instance, in Vanuatu, people with disabilities are three times more likely than people without disabilities to experience urinary incontinence but less able to use the toilet or bathe as often as required (Mactaggart et al., 2021; Wilbur et al., 2021a).

Improving physical access to WASH services for people with disabilities is important, but it is only part of the solution. Ensuring the meaningful participation of people with disabilities, providing accessible information, engaging and supporting caregivers, integrating disability-related activities and indicators in WASH policies and guidance documents, and supporting professionals to implement and monitor these are equally important (Wilbur et al., 2021a). “Meaningful participation” means expressing one's views, which influence the process of decision-making and the outcome (De Albuquerque, 2014).

These principles correspond to the “core concepts” of human rights, which are considered essential for universal, equitable, and accessible services within the EquiFrame policy analysis framework (Amin et al., 2011; Mannan et al., 2011). The EquiFrame is an analytical framework for assessing the commitment given to “vulnerable” groups and 21 core concepts of human rights in health policies (Mannan et al., 2011). The EquiFrame has also been adapted to focus on WASH, menstrual health, disability, and gender (Wilbur et al., 2019; Scherer et al., 2021). Core concepts of human rights, such as Participation, Affordability, Access, Protection against harm, and Integration, are included in or correlate to human rights principles in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCPRD), and the criterion used to specify the rights to water and sanitation (Rapporteur, 2008).

Disability and WASH in Cambodia

Cambodia's nationally-representative 2019 Demographic Health Survey (DHS), which incorporated the Washington Group Short Set questions, reported that 2.1% of the population age 5+ had a disability. The 2019 General Population Census reports a slightly lower prevalence of 1.2%, using the Washington Group Short Set. The census and the DHS found that the prevalence of disability increased with age and that people with disabilities face high levels of poverty and exclusion in several areas, including education and access to health services (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs, 2018; Palmer et al., 2019; National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, 2020).

The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) of the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (2017) reports that 29% of Cambodia's population do not have access to basic water supply, 31% do not have basic sanitation, and 26% do not have basic hygiene (WHO, UNICEF, 2017). Evidence about access to WASH for people with disabilities in Cambodia is limited but suggests that this population faces barriers including affordability, distance to the water source and latrine, and inaccessible infrastructure (MacLeod et al., 2014; Dumpert et al., 2018).

Commitments to progressively realizing the rights of persons with disabilities in Cambodia, including the rights to water and sanitation

The Royal Government of Cambodia has made significant efforts to progressively realize the rights of people with disabilities, including signing the UNCRPD in 2012 after ratifying it in 2017. The Government of Cambodia released the Cambodian Sustainable Development Goals (CSDGs) Framework in 2018, which explicitly includes people with disabilities in five targets and two indicators (Part 2: Target & Indicator Data Schedules) (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2018). In 2019, the Government launched its voluntary national review on the implementation of the CSDGs and marked that they were ahead of progress against two targets that referenced people with disabilities (Table 1 progress on CSDG) (Kingdom of Cambodia, 2019).

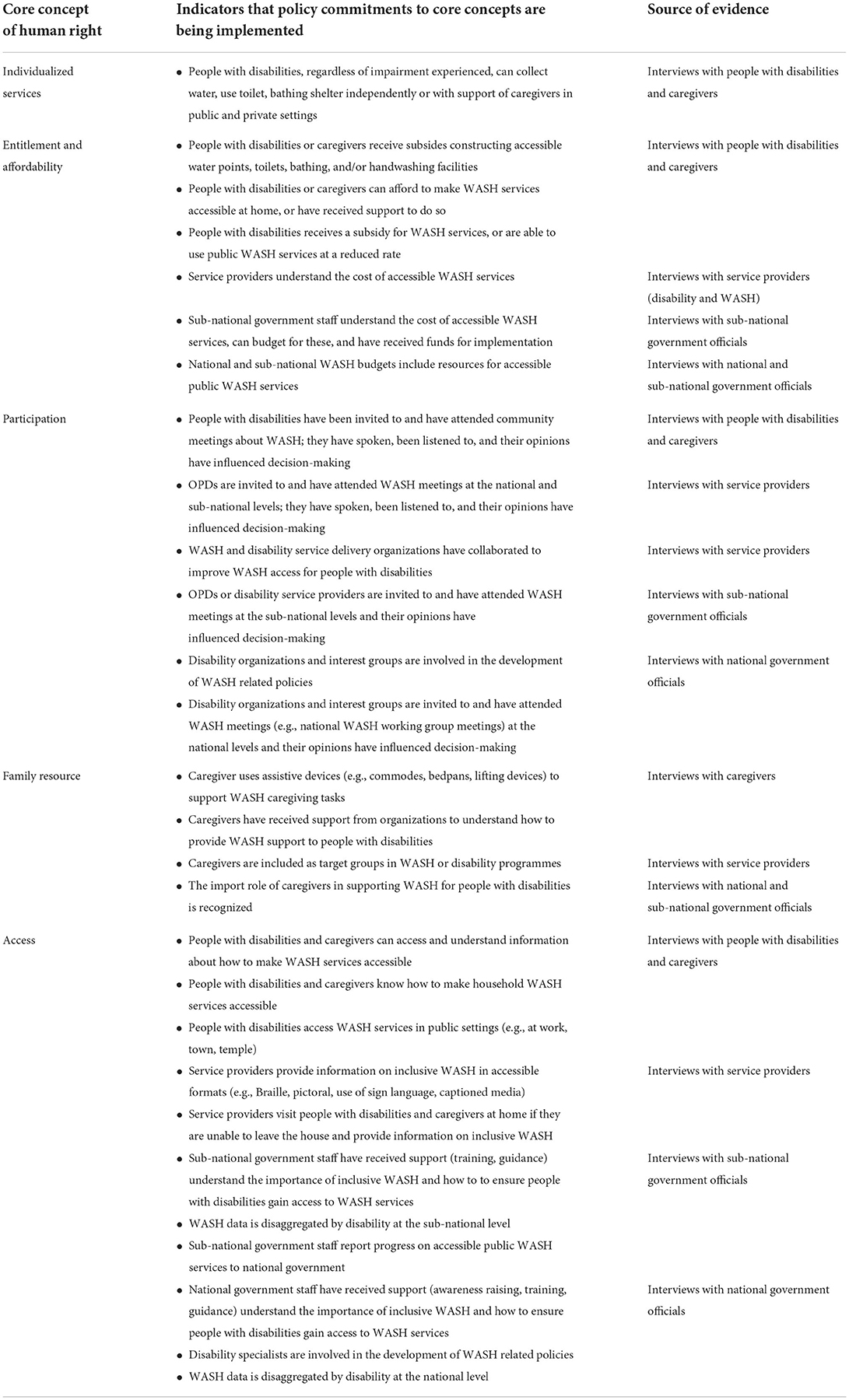

Table 1. Study indicators showing that policy commitments to core concepts are being implemented and the source of that evidence.

In 2009, the government adopted the ‘Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ (Kingdom of Cambodia, 2009) and introduced a monthly disability pension of 20,000 Riel (circa 5 USD), called Identification Card for Poor People (“IDPoor”), including people with severe disabilities living in poverty (Kingdom of Cambodia, 2011). The government also launched its National Disability Strategic Plan 2014–2018 and 2019–2023 (Royal Government of Cambodia, Disability Action Council, 2014, 2019) to improve the implementation of the National Disability Law and the CSDGs (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2014). This law included strategic objectives for equal access to clean water (1.4) and public toilets (8.1) (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2014); the National Disability Strategic Plan, 2019–2023 includes strategic objective 1.3.4 that ensures people with disabilities have access to affordable clean water services (Royal Government of Cambodia, Disability Action Council, 2019).

The Royal Government of Cambodia has made efforts to integrate disability within its WASH policies and guidance. For example, the National Strategy for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (2011–2025) states that ‘The needs of people with disabilities should be considered at all stages of the development process, including legislation, policies and programs, in any area, at all levels’ [page 9 (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2011)]. The government has adopted UNICEF's Three Star Approach for WASH in Schools (UNICEF, GIZ, 2013), whereby schools are awarded one to three stars if they progressively meet key minimum standards for “a healthy, hygiene-promoting school.” Three stars are awarded to schools where WASH facilities meet national standards, including ensuring they are accessible for children with disabilities. The National Guidelines on WASH for Persons with Disabilities and Older People (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2017) supports the implementation of commitments made in the National Strategy, the Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the CRPD.

Mechanisms to implement national WASH policy commitments

The Government of Cambodia is implementing a decentralization strategy, which focuses on developing the operational capacity of districts, municipalities (urban) and provinces (rural) under the supervision of national authorities (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2010). Commune councils (the lowest administrative level) are responsible for improving access to public services (including WASH, health services, and education), promoting social and economic development, and seeking funds for development projects (Ninh and Henke, 2005). Development priorities are set out in 5-year Commune Development Plans and annual Commune Investment Plans. Government officials, representatives of citizens, and civil society organizations, including Organizations of Persons with Disabilities, collaboratively develop these. Therefore, the commune plans are the vehicle to implement national-level commitments to disability-inclusive WASH.

Purpose of the study

The country site was identified from a list of countries of interest to the funder, that WaterAid works in and has good connections with government ministries, departments, and officials, as well as a strong network of WASH and disability service providers. We also wanted to select a country where some progress had been made in progressively realizing the right to water and sanitation for people with disabilities, where stakeholders would be willing to apply the learning generated through this study into practice, and where similarities could be observed with other LMICs.

Through discussions with specialists at WaterAid and the LSHTM, we identified Cambodia because the government has shown commitment to progressively realizing the right to water and sanitation for people with disabilities, demonstrated by laws, strategies, and guidelines referenced above. However, some gaps remain, including inadequate attention to hygiene behavior change, limited collaboration across WASH and disability sectors, and the perception that accessible WASH services are a “niche market” that diverts resources from large-scale sanitation efforts (Chenda Keo, 2014; MacLeod et al., 2014). Though limited evidence from other LMICs exists, an unpublished report of Malawi's WASH policies and practices to understand the inclusion of people with disabilities shows that many included policies reflected the rights-based approach to disability, but this was not borne out in practice (Biran and White, 2022). An accompanying qualitative study that explored the barriers faced by people with disabilities in accessing WASH services in Malawi found that accessible WASH services at the household level were limited (White et al., 2016).

Malawi and Cambodia operate a decentralized policy implementation system, as do many other LMICs, including Bangladesh, Tanzania, Vanuatu, and Nepal.

In 2021, we completed an analysis of Cambodia's WASH policies and guidance documents to assess the inclusion of disability rights using the EquiFrame policy analysis tool (Scherer et al., 2021). Findings show attention was given to 15 core concepts of human rights, including Individualized Services, Participation, Family Resource, and Access core concepts of human rights (Scherer et al., 2021). However, many included policies lacked clearly articulated actions to achieve these, leading the authors to conclude that policy implementation may fail to match stated aims.

The purpose of this study was to (1) explore the implementation of core concepts of human rights referenced in national WASH policies and guidance from the perspectives of national policymakers, local level implementers, service users with disabilities, and caregivers; (2) describe how these core concepts were implemented, highlighting any enablers and blockages, and (3) investigate how these efforts impact the WASH-related experiences of people with disabilities and their caregivers.

Materials and methods

Study design and research questions

This is a qualitative cross-sectional study in two provinces in Cambodia that aims to explore the implementation of core concepts of human rights through WASH service delivery efforts from the perspectives of policymakers, service providers, and intended service users. It uses respondents' descriptions to assess this and the impact efforts have on the WASH-related experiences of people with disabilities and their caregivers.

This study has two interrelated research questions:

1) To what extent are the commitments to core concepts of human rights referenced in the Government's national-level WASH policies and guidance implemented in the selected provinces by the sub-national government officials and service providers?

2) How does this implementation impact the experiences of people with disabilities and their caregivers?

The following five core concepts of human rights selected were either referenced highly in included policies or are integral to the WASH-related experiences of people with disabilities: Individualized services, Entitlement and affordability, Participation, Family resource, and Access. Table 1 presents these core concepts of human rights, indicators we used to explore if these core concepts referenced in WASH policies were implemented in the two provinces, and the source of evidence.

Study site

The study was conducted in selected urban and rural communities in the Svay Reing, and Kampong Chhnang Provinces. The 2014 Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey reported that 1.5% and 1.6% (respectively) of the population in these provinces have a disability (National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, ICF International, 2015). In the Svay Reing Province, 98% of the population has access to basic water and 92% has access to basic sanitation. This corresponds to 77% and 68% respectively in Kampong Chhnang (National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, 2020). No data on handwashing facilities at homes exist in either province. These provinces were selected because WaterAid is currently implementing the National Guidelines on Wash for Persons with Disabilities and Older People (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2017) in partnership with the national and sub-national governments and Organizations of Persons with Disabilities (OPDs) in Kampong Chhnang and Svay Reing. WaterAid also has a wide network of organizations in these provinces as it has worked with over 24 partners, including the Provincial government, civil society organizations (CSOs), OPDs, and private sector organizations over the past 5 years. Furthermore, WaterAid is committed to working in these provinces for the next 5 years, so will be able to integrate learnig from this study in their ongoing work.

Study population and sampling

We selected seven national and sub-national government officials and 10 service providers working in Phnom Penh, Svay Reing and Kampong Chhnang, 16 women and men with disabilities, and four female caregivers living in the two provinces. Table 2 presents details of the study population characteristics.

Replicating published methods used in Nepal (Wilbur et al., 2021b,c), we applied stratified purposive sampling (Patton, 2002) to select seven key informants to represent variation in seniority, geographic location, and sectors (health, education, WASH, and/or disability).

Key informants were identified through recommendations from WaterAid and the Cambodian Disabled People's Organization's (CDPO) networks as professionals with relevant knowledge of working in the WASH, health, education and disability sectors.

We purposively selected 16 individuals with disabilities from lists provided by sub-national OPDs that documented their members' (1) names, self-reported impairment experienced, age (18–65+ years), gender, and geographical location, and (2) names of caregivers who provide support to people with disabilities, gender, and geographical location. We aimed to achieve maximum heterogeneity by selecting 50% rural; 50% females with disabilities, impairment type, and province.

Data collection methods

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews carried out by pairs of interviewers (one lead and one support). To comply with social distancing guidance in the COVID pandemic, interviews were conducted remotely, via internet videoconferencing (for government officials) or telephone (for people with disabilities and caregivers). All interviews were conducted in Khmer, recorded on a voice recorder, and completed in 1 h or less.

Topic guides were prepared and used flexibly to explore core concepts of human rights with the study population. The topic guides for sub-national government officials, national government officials, disability service providers, WASH service providers, persons with disabilities, and caregivers are provided in Supplementary materials 1–6, respectively.

Regarding safeguarding, an algorithm outlining referral options or actions to be taken in response to disclosures of violence was annexed to the topic guides (see Supplementary materials 5, 6). Furthermore, a key challenge related to remote data collection via the telephone is an inability to see participants' visual cues, which, as Hensen et al. (2021) note, may reduce understanding and appropriate prompting. Researchers managed this by actively listening for changes in participants' tone or prolonged pauses in the conversation, as these could be indicators of stress or distress. When incidences arose, researchers offered to pause, end or rearrange the interview for a later date.

Data analyses

Data analyses were iterative. Recordings of interviews were translated and transcribed within 2 weeks of completing the interview so that data could be analyzed during collection. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by the interviewers; revisions were made before finalization.

Two authors thematically analyzed all transcriptions. This involved (1) familiarization with the data, (2) initial coding according to pre-determined codes which reflected the issues explored in the topic guides (e.g., Participation, Entitlement and Affordability, Access), (3) iteratively identifying additional codes, (4) developing an analytical codebook to organize data for interpretation, (5) double-coding a small amount of data to refine the codebook content and ensuring coding template (O'Connor and Joffe, 2020), (6) coding all transcripts, (7) comparing researcher codes, discussing and agreeing on final codes, (8) reviewing the relationships between the codes and discussing analyses with the broader research team. Nvivo 12 was used to organize data and capture analyses. Quotes, codes, and high-level analysis of these quotes were captured in an excel spreadsheet.

Informed consent process

At the start of the interview, the researchers sought informed consent from all participants. Information and consent sheets were emailed to government officials and service providers before the meeting, and written consent was sought. Verbal consent was sought from people with disabilities and caregivers over the telephone. The interview proceeded if consent was provided.

The research team

The research team consisted of academics from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (who remained in the UK for the study), WASH professionals working for WaterAid in Cambodia, a disability rights activist employed by CDPO, and a freelance researcher. The latter two have a disability.

One of the four-person team was an experienced qualitative researcher but limited WASH knowledge. The other team members were experienced in WASH but not qualitative methods. Therefore, the topic guides provided detailed guidance on what issues to explore during interviews. Additionally, the team met prior to interviewing key informants to identify any issues that were irrelevant to the participant's role and responsibilities.

Some key informants had previously interacted with WaterAid and CDPO. In these cases, a team member working for a different organization led the interview and reiterated confidentiality throughout the interview process to encourage honest answers.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval for the study at the LSHTM (reference: 17679-3) and the National Ethics Committee for Health Research in Cambodia (reference: 160).

Results

Participation

At the national level, government officials regarded the participation of OPD staff with disabilities in WASH sector meetings as essential to ensure people with disabilities' requirements and priorities were reflected in WASH activities.

“…if there are any [meetings] or events, we always invite people from all the backgrounds, especially the people with disabilities, to participate” (National government official).

This quote demonstrates that the national government official thinks that participation of people with disabilities is desirable and inviting OPD staff to attend national WASH sector meetings is a means of achieving this. National-level OPD staff confirmed they had been invited to such meetings but sometimes lacked the time and space to engage effectively. Therefore, they prefer separate meetings where disability inclusion is discussed in more depth.

“Normally, in a big meeting like that, the time is set, and we do not have enough time to voice our opinions. However, if we have a separate meeting for us [….]I think it seems-it's working better” (National level Organization of Persons with Disabilities).

The following quote, given by the same national government official quoted above, highlights that they believe that people with disabilities participate in implementing WASH interventions at the sub-national level.

“Any implementation plans require the participation of the sub-national level. Thus, if there are any conditions or events, we always invite […] people with disabilities to participate in planning-as you already know, only the disabled people understand their needs. Only they know what they want. If we just prepare for them, it will not be right unless they have their own voice of what they want” (National government official).

However, a government official at the sub-national level expressed a different perspective.

“To be honest, on the provincial level, it is very rare to meet [people with disabilities]. There were never people with disabilities attending conferences or meetings” (Province government official).

Sub-national OPD staff explained that they were sometimes invited to sub-national meetings to serve as representatives for the broader disability community. Some OPD staff noted that raising the requirements of people with disabilities at Commune Investment Plan meetings was difficult because meeting attendees expected the OPDs to solve the issues they raised. This was not possible, partly because the OPDs lacked the financial resources and influence. Further, some staff reported facing backlash from meeting attendees when voicing the needs of people with disabilities at sub-national planning meetings.

“They talk with their group […]: ‘Every time she comes to the meeting there are always problems for [us] to solve with a lot of headaches and [we] cannot solve’. [..] They said that […] So, they do not really want to see my face-do not really want to invite me to the meeting. [….]

“We work without salary and we just raise the problems. It is too difficult. [….], too much headache. We do not even have the money for gas and people look down on us too. Do not even have the salary. It is hopeless” (Sub-national OPD staff member).

Interviews with people with disabilities and caregivers revealed that very few respondents with disabilities had attended WASH meetings in their community. Barriers included never having been invited, difficulties reaching the meeting location, reliance on caregivers to take them to the meeting, that caregivers are not given financial assistance or transport to attend with the person with disabilities, and a lack of assistive devices (e.g., wheelchair) to support mobility. The latter was raised by many participants with disabilities and their caregivers as a significant barrier to leaving home. If these individuals were not visited in their homes, they were unable to participate:

“The reason [I don't take him out of the house] is it is difficult to do so […….] How can he go out when he cannot walk and sit? And, I cannot carry him out. [….] It is just that I take care of him. I bathe him, give him food, etc. No one brings him out. […]

“The reason [we have never gone to meetings on WASH] is we always stay home and never participated in anything. So, we do not know” (Caregiver of a man with a mobility impairment).

A woman with a visual impairment expressed her loneliness because she could not leave her home and interact with others.

Participant: “I never talk to anyone. I just stay at home like a frog in a well.”

Researcher: “You only stay at home and cannot communicate with anyone?”

Participant: “Right, I have never been anywhere. I have blindness, so I cannot go anywhere.”

There was an example of a WASH organization and OPD co-leading a community WASH meeting and encouraging the meaningful participation of people with disabilities. A person with cognitive and mobility impairments and her caregiver attended this meeting. The caregiver noted how the two organizations spent time explaining information clearly to the person with disabilities.

“They knew she was like this, so they paid attention to her. They explained to everyone, just focused on explaining to her clearer than to others” (Caregiver of a woman with cognitive and mobility impairments).

Individualized services, access, and entitlement and affordability

This section relates to people with disabilities access to accessible WASH services and information in schools and households. The ability to afford these services influences access for people with disabilities, so results related to these core concepts are discussed together.

Concerning access to accessible WASH services in schools, many key informants highlighted UNICEF's Three Star Approach for WASH in Schools (UNICEF, GIZ, 2013) as an example of achieving this. For instance, a national government official explained progress in this area by citing data gathered through this approach.

“We have seen that there are 77.4% of schools which, at least, has 1 star up to 3 stars. we have seen an increase of over 4% per year, which is something to be proud of” (National government official).

Service delivery organizations also cited the Three Star Approach as an example of how their organization works toward ensuring children with disabilities have access to WASH in schools. These included participants who work for NGOs that do not specifically focus on disability but work with ‘vulnerable groups’.

“Our goal is that every school that we build the toilets for, they must get three stars” (NGO staff member).

At the household level, the following results indicate that policy commitments about improving access to affordable WASH services that everyone can use do not always lead to improvements for people with disabilities and their caregivers. For instance, most participants reported that they needed piped water, accessible toilets and bathing facilities, but very few could afford them, as expressed by a man with a mobility impairment:

Participant: I want a bigger toilet so that the wheelchair can go in and stuff, but I do not have the money.

Researcher: I see. You do not install a railing?

Participant: No, where can I get the money for that when I do not have any money?

Participants with disabilities rarely earned an income in the formal or informal sectors. If caregivers provided full-time support to individuals, they too could not work. The few families that received a cash transfer through “IDPoor” noted the challenges faced in accessing it, including physically getting a person with disabilities to the bank to have their photo taken and an inability to afford transport to the bank to collect payments.

Many participants had wells near their homes, so water quantity was not an issue for those who could collect water independently. However, few adaptations were made to make the waterpoint more accessible, such as leveling the path from the household to the well and building a ramp to the waterpoint to enable wheelchair access. Many people with mobility, cognition and visual impairments relied on others to collect their water and put it in a place they could easily locate and reach.

Few participants with disabilities could independently and safely access and use bathing and toilet facilities at home. Most did not know what adjustments could be made to make facilities more accessible, how to make them, or whom to talk to.

“I do not know what we can do when he only has one hand and he is not strong enough. If I let him do it himself, I am afraid that he might fall” (Proxy interview with a caregiver of a man with a mobility impairment).

There are examples of simple innovations to support access to WASH in households, developed by people with disabilities or their families. For instance, piping water to the bed for independent bathing or constructing a railing to guide a man with a visual impairment to a bathroom outside.

“Even when I have a bit of diarrhea, I could get [to the toilet] faster too because I have what I have built for my needs. It is easy, not difficult at all (chuckles) Just hold the bamboos and walk along. I can walk quickly like people who can see. Nothing seems to be of obstacle for me” (Man with visual impairment).

People with disabilities reported not bathing as often as they wished, especially those reliant on caregivers. One caregiver explained they cannot wash the person with disabilities as often as the rest of the family bathe “because I am busy and it is hard.” Caregivers also expressed how vital keeping clean is for positive social interactions:

“I want him to be clean so that others do not say that he is dirty and not good, and do not want to talk to or stay near him” (Caregiver of a man with cognitive impairments).

Family resource

WASH tasks completed by caregivers included collecting and storing water for the individual's bathing and drinking needs, which participants reported being time-consuming and physically demanding. Many caregivers support people to urinate and defecate by assisting them in reaching the toilet, supporting toileting in bed, and cleaning the body or clothing after urination or defecation.

Many caregivers provide full-time support to individuals without any training or guidance. They essentially developed their own care practices. Few had assistive devices, such as commodes or bedpans to support toileting, so caregivers and people with disabilities who could not sit out of bed unaided regularly came into contact with urine and feces. For instance, one caregiver of an individual who cannot sit out of bed unaided fashioned a hole in the person with disabilities' bed, so they could defecate there without having to be moved. The caregiver would then dispose of the feces.

No caregiver had assistive products, such as lifting devices, which would enable them to safely support the person with disabilities and with limited risk to themselves. Many caregivers explained how physically demanding it is to move people with mobility limitations, especially adults. Some caregivers, including one who had recently given birth, explained the WASH-related tasks performed and their concerns about how they will cope when the individual grows and gets heavier.

“I am worried that when she gets older, it will be harder for me to lift her up […]. “I lift her back and forth. She is not a small child. She is almost 20 kg; not small. Other people who just gave birth would not lift her like this, but if I do not do it, no one else would” (Caregiver of a woman with a mobility impairment).

However, in interviews with government officials and service providers, only one OPD highlighted caregivers' critical role in supporting people with disabilities' WASH needs. None said they work to support caregivers to carry out this role.

Discussion

This study explored the implementation of core concepts of human rights referenced in Cambodia's WASH policies and guidance and the WASH-related experiences of people with disabilities and their caregivers in two provinces. The Three Star Approach to WASH in schools is a promising example of how policy commitments could be implemented if they include specific targets and if these are systematically delivered, monitored and reported on. However, most of this study's findings illustrate that the Government of Cambodia's policy commitments to progressively realize the rights of persons with disabilities to water and sanitation are not necessarily borne out systematically across national, sub-national, and household levels. Challenges include difficulties faced by OPDs in advocating for the rights of persons with disabilities to water and sanitation in provincial system planning meetings, inadequate access to assistive devices (e.g., wheelchair) and inaccessible terrain, meaning many people with disabilities were unable to leave home or reach the WASH meeting venue, and limited support provided to get people to the meeting and then participate meaningfully. People with disabilities in our sample have inadequate WASH services at home, and many participants relied on others to collect water and support access to latrines and bathing facilities. People with disabilities and caregivers cited an inability to afford accessible WASH services and a lack of information and knowledge about ways to improve access for people with disabilities. Many caregivers supported individuals in collecting water, bathing, and toileting, which they reported as physically demanding and time-consuming. Caregivers had no guidance about how to carry out the role, had few assistive devices (such as bedpans and commodes) or products (i.e., lifting devices), and key informants supported none to carry out this role.

Participation

Existing evidence demonstrates that, if supported to participate effectively, OPDs can play an essential and positive role in furthering the rights of persons with disabilities (Young et al., 2016; Grills et al., 2020). Young et al. (2016) literature review about the roles and functions of OPDs in low- and middle-income countries found evidence that OPDs can have significant and positive outcomes for people with disabilities, especially in employment, participation in training interventions, accessing microfinance and bank loans and involvement in civil society. A randomized control trial that aimed to measure the effectiveness of OPDs in improving people with disabilities' wellbeing in India found positive correlations between OPD involvement and increased participation, access to services (including sanitation), and wellbeing of the study population (Grills et al., 2020).

However, many studies highlight less optimal involvement of OPDs in policy and practice processes, including a study which reviewed the OPDs' participation in Ghana's Disability Fund, which provides financial support to people with disabilities through its decentralized political structures (Opoku et al., 2018). National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning (2020) found that OPDs were not fully consulted in the allocation grants, even though they were for people with disabilities (Opoku et al., 2018).

Our study highlighted challenges related to the ability of OPDs to meaningfully participate in meetings for various reasons. For instance, OPDs were expected to solve issues facing people with disabilities that they raised and sub-national planning meetings, even though they are often under-resourced and regarded as having limited status. Findings from other studies in different settings similarly highlight that OPDs are increasingly engaged in or expected to engage in a wide array of activities, including service delivery roles typically performed by the state, often with limited financing (Young et al., 2016; Cote, 2020; Grills et al., 2020). This finding is also noted in a forthcoming study that analyses data from nine population-based surveys in LMICs, leading authors to conclude that people with disabilities may not be accessing public services as a result (Banks et al., 2020).

These challenges make it difficult for sub-national OPDs in our study to advocate for change and raise public awareness about disability rights, which is a core role of ODPs (Grills et al., 2020). If OPDs are not given more significant support and resources in Cambodia, there is a risk that they might either stop attending the meetings or advocating for people with disabilities. As the Government of Cambodia is ratified the UNCRPD, it should work toward achieving Article 29 of the UNCRPD (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2008), which specifies that State Parties:

“b) To promote actively an environment in which persons with disabilities can effectively and fully participate in the conduct of public affairs, without discrimination and on an equal basis with others, and encourage their participation in public affairs, including:

ii. Forming and joining organizations of persons with disabilities to represent persons with disabilities at international, national, regional and local levels.”

In practice, this should include state actors and civil society's investment in OPD's long-term sustainability, including funding core costs, capacity enhancement, and, as Cote (Cote, 2020) recommends assisting the organization to diversify its funding base to ensure its autonomy and independence.

At the household level, people with disabilities and caregivers should be supported to attend WASH meetings in the community. For instance, transport could be provided to take people unable to leave home, or staff should visit these households so that all people can influence WASH-related decisions that will affect them. Information must be communicated in accessible formats, and people with disabilities should be given space and time to contribute their opinions. Results from a cluster-randomized trial to evaluate the impact of an inclusive community-led total sanitation (CLTS) intervention in Malawi showed that people with disabilities were more likely to attend community meetings and construct or adapt household latrines, so they were accessible for people with disabilities in the intervention arm (Biran et al., 2018). Efforts which led to these results included training facilitators on inclusive implementation of CLTS (Biran et al., 2018). This involved awareness-raising on disability and the WASH requirements of people with disabilities, methods to ensure people with disabilities participate in decision making, techniques to make sanitation facilities accessible, how to provide accessible information, and conducting house-to-house visits for people unable to leave the home (Biran et al., 2018). An inability to leave home was a reality for many participants with disabilities in our study, suggesting that investing in visiting people in their homes is desirable.

Individualized services, access, and entitlement and affordability

Access to accessible and affordable WASH in households, schools, public places, and workplaces is essential to participation. Our analysis of Cambodia's WASH policies and guidance (Scherer et al., 2021) indicated that the country's WASH in schools' policy commitments, targets and indicators related to disability are relatively strong (Scherer et al., 2021). The Three Star Approach for WASH in Schools (UNICEF, GIZ, 2013) appears to support monitoring the implementation of those commitments. This is because government officials and service providers, including those that do not explicitly focus on disability, are applying the tool and supporting schools to progress to the three-star status, which includes accessible latrines.

The Three Star Approach for WASH in Schools could potentially improve access to WASH services at school for children with disabilities who are in education. However, the Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey data, reported in the UN Disability and Development Report (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs, 2018), notes wide disparities in education for children with disabilities, whereby only 44% of children with disabilities completed primary education, compared to 73% of their peers without disabilities (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs, 2018). Such disparities, which increase from primary to secondary school, are evidenced in many other countries (Kuper et al., 2014; Mizunoya et al., 2018).

Our sampling was not intended to be statistically representative, so we could not meaningfully explore access to education and inclusive school WASH for participants with disabilities. However, we found that many people with disabilities could not leave home because of a lack of assistive devices and inaccessible terrain. This is reflected in many other studies (Sheppard and Polack, 2018; Banks et al., 2019; Mactaggart et al., 2021), including a scoping review that explored the barriers and facilitators to participation for children and adolescents with disabilities in LMICs (Huus et al., 2021). Huus et al. (2021) noted inaccessible school facilities and transport, poor roads and infrastructure, negative teachers' attitudes, financial implications, and lack of access to assistive devices as barriers to participation, including education (Huus et al., 2021). Therefore, attention to and investment in making school WASH facilities physically accessible in Cambodia is one component of realizing Access, but more must be done. Resources must be allocated to ensure people with disabilities can access and use WASH facilities in or near the home.

The human rights framework state that water and sanitation must be affordable (not free), requiring a safety net for those who cannot afford to pay (full) costs' [p. 78 (De Albuquerque, 2014)]. Our study shows that many people with disabilities cannot afford to make household WASH facilities accessible and have no information about how to make low-cost adaptations to improve accessibility. As adults with disabilities are 50% less likely to be employed than adults without disabilities (World Health Organization, 2011), more significant efforts must be taken to support affordability for this population and increase awareness of low-cost household WASH technology options. Efforts should draw on Cambodia's National Guidelines on WASH for persons with disabilities and older adults, specifically the “accessible designs” sections for handwashing stations (page 31–32) and water supply (page 38–39) (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2017), as well as resources for other resource-poor settings (Jones and Wilbur, 2014; Government of India, Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation SBMG, 2015; Coultas et al., 2020). Service providers should systematically disseminate information through national WASH working group and Commune Investment Plan meetings, mass media campaigns via radio, television, and print, through visiting people with disabilities and their caregivers at home and community WASH meetings.

Family resource

Caregivers are vital to enabling people with disabilities who need assistance to meet their WASH needs and participate in daily life. Still, our policy analysis and this study highlight that caregiver's role is underappreciated within Cambodia's WASH policies, guidance or implementation (Scherer et al., 2021). This absence has several vital impacts. Firstly, when caregivers are not supported to understand how to provide WASH care hygienically and with dignity and do not have access to assistive devices to help toileting (such as lifting devices, commodes, and bedpans), their own mental and physical health and wellbeing suffer, as well as that of the individual they support. Similar impacts are observed in Pakistan, Vanuatu, Nepal, India, and Malawi, where some caregivers reported that providing long-term care can be rewarding but also that it incurs physical and psychological impacts (White et al., 2016; Ansari, 2017; Thapa and Sivakami, 2017; Wilbur et al., 2021a,c). Consequently, some people with disabilities were neglected, physically and verbally abused, ashamed, and socially isolated (White et al., 2016; Ansari, 2017; Thapa and Sivakami, 2017; Wilbur et al., 2021a,c,d). Across all settings, individual innovations to make WASH more accessible exist, but organized support is absent. Secondly, if caregivers who provide full-time support are not resourced to attend meetings, they must incur additional financial costs. It is likely that the household already experiences income poverty, so not facilitating attendance risks excluding these families from WASH meetings.

Bringing it all together

Our findings show that implementing disability-inclusive policy commitments may be possible if clear and consistent steps to achieve these are identified and service delivery organizations systematically work to realize them. However, efforts must be taken to support OPDs to advocate for disability rights at WASH sector meetings and invest in OPDs' long-term sustainability and capacity enhancement. At the commune and household level, greater support is required to enable people with disabilities and families to attend and meaningfully participate in WASH meetings, access to WASH facilities at home that can be used as independently as possible, as well as assist caregivers in their role to support WASH for people with disabilities.

Finally, our findings show that people with disabilities face discrimination in many areas of their life, including accessing WASH services. Discrimination experienced in areas such as health services, including assistive devices, education, and employment, can all impact a person's access to WASH services. Therefore, improving access to WASH services must be considered within the broader context. WASH sector professionals must connect with disability service providers and rights organizations to challenge disability discrimination more broadly. For example, WASH and disability service providers should collaborate to support livelihood programmes for people with disabilities to finance adjustments to make WASH services accessible and provide accessible information about such adaptations. They must also coordinate efforts to improve access to assistive devices and products to enable people with disabilities to reach WASH facilities and caregivers to support toileting and bathing more safely. In conclusion, a more comprehensive approach to progressively realizing the rights to water and sanitation for people with disabilities could significantly disrupt the vicious cycle of poverty and disability.

Study strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study was that results from our previous policy analysis (Scherer et al., 2021) fed into identifying issues to explore, developing topic guides, and analyzing this study's findings. Data collection was conducted by Cambodians with and without disabilities with professional experience in WASH, disability, and qualitative research methods. The study population was comprehensive as we interviewed a range of key informants from the national and district level, women and men with various impairments, and their caregivers.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting these results. The COVID-19 pandemic meant we could not generate data in person and had to conduct interviews over the phone or online. This may have limited the rapport researchers could develop with participants and meant that we could not carry out methods triangulation. Some key informants knew the organization the researchers worked for, which could have influenced their responses. This was managed by reiterating confidentiality and anonymity of responses during the interview.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK) and National Ethics Committee for Health Research (Cambodia). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JW: literature search, study conceptualization, study design, data collection oversight, verification of underlying data, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. PP, RH, and SN: data collection oversight, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript review. CH, LB, NS, and AB: data interpretation and manuscript review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade's Water for Women Fund (grant number: WRA1), under the project Translating disability-inclusive WASH policies into practice: lessons learned from Cambodia and Bangladesh.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the participants who shared their experiences openly with us. We would like to thank and acknowledge the contribution of Vaanda Slout, who was part of the research team and contributed throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia accepts no responsibility for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on any of the information or views in this publication.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2022.963405/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary material 1. Topic guides for sub-national government officials.

Supplementary material 2. Topic guide for national government officials.

Supplementary material 3. Topic guide for disability service providers.

Supplementary material 4. Topic guide for WASH service providers.

Supplementary material 5. Topic guide for people with disabilities.

Supplementary material 6. Topic guide for caregivers.

References

Amin, M., MacLachlan, M., Mannan, H., El Tayeb, S., El Khatim, A., Swartz, L., et al. (2011). EquiFrame: a framework for analysis of the inclusion of human rights and vulnerable groups in health policies. Health Human Rights. 13, 1–20. Available online at: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2013/08/equiframe-a-framework-for-analysis-of-the-inclusion-of-human-rights-and-vulnerable-groups-in-health-policies/

Ansari, Z. (2017). Understanding the Coping Mechanisms Employed by People With Disabilities and Their Families to Manage Incontinence in Pakistan [MSc]. LSHTM.

Banks, L. M., Eide, A., Hunt, X., Abu Alghaib, O., and Shakespeare, T. (2020). How Representative are Organisations of Persons with Disabilities? Data from Nine Population-Based Surveys in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. World Development Forthcoming.

Banks, L. M., White, S., Biran, A., Wilbur, J., Neupane, S., Neupane, S., et al. (2019). Are current approaches for measuring access to clean water and sanitation inclusive of people with disabilities? Comparison of individual- and household-level access between people with and without disabilities in the Tanahun district of Nepal. PLoS ONE 14, e0223557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223557

Biran, A., Danquah, L., Chunga, J., Schmidt, W. P., Holm, R., Itimu-Phiri, A., et al. (2018). A Cluster-Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Impact of an Inclusive, Community-Led Total Sanitation Intervention on Sanitation Access for People with Disabilities in Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene 98, 984–94. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0435

Biran, A., and White, S. (2022). Improving Access to WASH for People With Disabilities in Malawi. A review of policy and practice.

Cote, A. (2020). The Unsteady Path. Towards Meaningful Participation of Organisations of Persons With Disabilities in the Implementation of the CRDP and SDGs. A pilot study by Bridging the Gap. Madrid.

Coultas, M., Iyer, R., and Myers, J. (2020) Handwashing Compendium for Low Resource Settings: A Living Document. Brighton: The Sanitation Learning Hub Institute of Development Studies. doi: 10.19088/SLH.2020.008

De Albuquerque, C. (2014). Realising the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: A Handbook by the UN Special Rapporteur: Principles.

Dumpert, J., Gelbard, S., Huggett, C., and Padilla, A. (2018). WASH Experiences of Women Living with Disabilities in Cambodia. CRSHIP: Issue Brief.

Government of India, Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation SBMG. (2015). Handbook on Accessible Household Sanitation for Persons with Disabilities (PwDs). Delhi.

Grills, N. J., Hoq, M., Wong, C-P. P., Allagh, K., Singh, L., et al. (2020). Disabled People's Organisations increase access to services and improve well-being: evidence from a cluster randomized trial in North India. BMC Public Health. 20:145. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8192-0

Hensen, B., Mackworth-Young, C. R. S., Simwinga, M., Abdelmagid, N., Banda, J., Mavodza, C., et al. (2021). Remote data collection for public health research in a COVID-19 era: ethical implications, challenges and opportunities. Health Policy Plan. 36, 360–368. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa158

Huus, K., Schlebusch, L., Ramaahlo, M., Samuels, A., Berglund, I. G., Barriers, D., et al. (2021). and facilitators to participation for children and adolescents with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries - A scoping review. Afr. J. Disabil. 10:771. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v10i0.771

Kingdom of Cambodia (2011). Policy on the Disability Pension for the Poor Disabled People. Phnom Penh.

Kingdom of Cambodia (2019). Cambodia's Voluntary National Review 2019 on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/23603Cambodia_VNR_SDPM_Approved.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022).

Kingdom of Cambodia. (2009). Law on the Protection and the Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Phnom Penh.

Kuper, H., Monteath-van Dok, A., Wing, K., Danquah, L., Evans, J., Zuurmond, M., et al. (2014). The impact of disability on the lives of children; cross-sectional data including 8,900 children with disabilities and 898,834 children without disabilities across 30 countries. PLoS ONE 9:e107300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107300

MacLeod, M., Pann, M., Cantwell, R., and Moore, S. (2014). Issues in access to safe drinking water and basic hygiene for persons with physical disabilities in rural Cambodia. J. Water Health 12, 885–895. doi: 10.2166/wh.2014.009

Mactaggart, I., Baker, S., Bambery, L., Iakavai, J., Kim, M. J., Morrison, C., et al. (2021). Water, women and disability: Using mixed-methods to support inclusive wash programme design in Vanuatu. Lancet Region. Health 8:100109. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100109

Mactaggart, I., Schmidt, W.-P., Bostoen, K., Chunga, J., and Danquah, L. (2018). Access to water and sanitation among people with disabilities: results from cross-sectional surveys in Bangladesh, Cameroon, India and Malawi. BMJ Open 8:e020077. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020077

Mannan, H., Amin, M., MacLachlan, M., El Tayeb, S., El Khatim, A., Bedri, N., et al. (2011). The EquiFrame Manual: A Tool for Evaluating and Promoting the Inclusion of Vulnerable Groups and Core Concepts of Human Rights in Health Policy Documents. Dublin: The Global Health Press.

Mizunoya, S., Mitra, S., and Yamasaki, I. (2018). Disability and school attendance in 15 low- and middle-income countries. World Dev. 104, 388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.001

National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, ICF International (2015). Cambodia Demographic Health Survey 2014. Phnom Penh; Rockville, MD: National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, and ICF International.

National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning (2020). General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2019 National Report on Final Census Results. Phnom Penh.

Ninh, K., and Henke, R. (2005). COMMUNE COUNCILS IN CAMBODIA A National Survey on their Functions and Performance, With a Special Focus on Conflict Resolution. The Asia Foundation.

O'Connor, C., and Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Q. Methods 19:1609406919899220. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, (2008). Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities.

Opoku, M. P., Nketsia, W., Agyei-Okyere, E., and Mprah, W. K. (2018). Extending social protection to persons with disabilities: Exploring the accessibility and the impact of the Disability Fund on the lives of persons with disabilities in Ghana. Global Soc. Policy 19, 225–45. doi: 10.1177/1468018118818275

Palmer, M., Williams, J., and McPake, B. (2019). Standard of living and disability in Cambodia. J. Dev. Stud. 55, 2382–2402. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2018.1528349

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rapporteur, U. S. (2008). Frequently Asked Questions: The Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation.

Royal Government of Cambodia (2010). National Program fo Sub-National Democratic Development (NP-SNDD) 2010–2019.

Royal Government of Cambodia (2011). National Strategy for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene 2011-2025. In: Ministry of Rural Development, editor. Phnom Penh.

Royal Government of Cambodia (2014). Cambodia National Disability Strategic Action Plan, NSDP, 2014-2018. In: Disability Action Council, Ministry of Social Affairs VaYR, editors. Phnom Penh.

Royal Government of Cambodia (2018). Cambodian Sustainable Development Goals (CSDGs) Framework (2016-2030) (unofficial translation). Available online at https://dac.gov.kh/en/download.html (accessed August 1, 2022).

Royal Government of Cambodia, Disability Action Council (2014). National Disability Strategic Plan (2014-2018). Available online at: https://dac.gov.kh/images/pictures/pdf/english/National-Disability-Strategic-Plan-2014-2018.pdf (accessed August 2, 2022).

Royal Government of Cambodia, Disability Action Council (2019). National Disability Strategic Plan (2019–2023).

Royal Government of Cambodia. (2017). National Guidelines on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Persons with Disabilities and Older People In: Ministry of Rural Development, editor. Phnom Penh.

Scherer, N., Mactaggart, I., Huggett, C., Pheng, P., Rahman, M., Biran, A., et al. (2021). The inclusion of rights of people with disabilities and women and girls in water, sanitation, and hygiene policy documents and programs of Bangladesh and Cambodia: Content analysis using EquiFrame. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:e105057. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105087

Sheppard, P., and Polack, S. (2018). Missing Millions: How Older People With Disabilities are Excluded From Humanitarian Response. London: HelpAge International.

Thapa, P., and Sivakami, M. (2017). Lost in transition: menstrual experiences of intellectually disabled school-going adolescents in Delhi, India. Waterlines 36, 317–38. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.17-00012

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018). Disability and Development Report. Realising the Sustainable Development Goals by for and With Persons With Disabilities.

White, S., Kuper, H., Itimu-Phiri, A., Holm, R., and Biran, A. (2016). A qualitative study of barriers to accessing water, sanitation and hygiene for disabled people in Malawi. PLoS ONE 11:e0155043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155043

WHO, UNICEF (2017). Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva: WHO.

Wilbur, J., Kayastha, S., Mahon, T., Torondel, B., Hameed, S., Sigdel, A., et al. (2021c). Qualitative study exploring the barriers to menstrual hygiene management faced by adolescents and young people with a disability, and their carers in the Kavrepalanchok district, Nepal. BMC Public Health 21:476. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10439-y

Wilbur, J., Morrison, C., Bambery, L., Tanguay, J., Baker, S., Sheppard, P., et al. (2021a). “I'm scared to talk about it”: exploring experiences of incontinence for people with and without disabilities in Vanuatu, using mixed methods. Lancet Region. Health 14:100237. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100237

Wilbur, J., Morrison, C., Iakavai, J., Shem, J., Poilapa, R., Bambery, L., et al. (2021d). “The weather is not good”: exploring the menstrual health experiences of menstruators with and without disabilities in Vanuatu. Lancet Region. Health 2021:e100325. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100325

Wilbur, J., Scherer, N., Mactaggart, I., Shrestha, G., Mahon, T., Torondel, B., et al. (2021b). Are Nepal's water, sanitation and hygiene and menstrual hygiene policies and supporting documents inclusive of disability? A policy analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2021:20. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01463-w

Wilbur, J., Torondel, B., Hameed, S., Mahon, T., and Kuper, H. (2019). Systematic review of menstrual hygiene management requirements, its barriers and strategies for disabled people. PLoS ONE 14:e0210974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210974

World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2021). Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000-2020: Five Years Into the SDGs. Geneva.

Keywords: disability, water, sanitation and hygiene, policy, service delivery, Cambodia

Citation: Wilbur J, Pheng P, Has R, Nguon SK, Banks LM, Huggett C, Scherer N and Biran A (2022) A qualitative cross-sectional study exploring the implementation of disability-inclusive WASH policy commitments in Svay Reing and Kampong Chhnang Provinces, Cambodia. Front. Water 4:963405. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2022.963405

Received: 07 June 2022; Accepted: 23 August 2022;

Published: 15 September 2022.

Edited by:

Yizi Shang, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, ChinaReviewed by:

Ojima Wada, Hamad bin Khalifa University, QatarSurapaneni Krishna Mohan, Panimalar Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, India

Puthearath Chan, Zaman University, Cambodia

Subodh Sharma, Kathmandu University, Nepal

Jennifer R. McConville, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden

Copyright © 2022 Wilbur, Pheng, Has, Nguon, Banks, Huggett, Scherer and Biran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jane Wilbur, SmFuZS53aWxidXJAbHNodG0uYWMudWs=

Jane Wilbur

Jane Wilbur Pharozin Pheng3

Pharozin Pheng3 Adam Biran

Adam Biran